|

*

Steam Locomotive No. 844, Del Rio, TX (Photo inset

above) “Steam Locomotive No. 844 is the last steam locomotive built for Union

Pacific Railroad. It was delivered in 1944. A high-speed passenger engine, it

pulled such widely known trains as the Overland Limited, Los Angeles Limited,

Portland Rose and Challenger trains.”

STEAM LOCOMOTIVES

http://jonelder.com/steam-locomotive-comes-to-town/

* Special thanks to "Google Images", "The Atlantic", "Wikipedia.com"

and all the institutions dedicated to the preservation for the history of railroading.

and all the institutions dedicated to the preservation for the history of railroading.

BLOG POST

by Felicity Blaze Noodleman

Los Angeles, CA

10.18.13

This is another adventure into the past – we admit out love

for history and “Americana”. Our

subject this week is the American Steam Locomotives of yesteryear, their evolution

and eventual demise. They were spanned a history of over 120 years and presided over the growth of a nation.

The United States was still in its infancy and little more

than a Colonial Nation when the first steam locomotives began to change the country’s

destiny and bringing the future into reality and connecting all points in the

country together until the Railroads connected the Atlantic ocean in the East

coast and Pacific ocean in the West coast at Promontory Summit, Utah where a

golden spike was driven into the last rail to complete the nation’s first coast

to coast transcontinental railroad.

With the invention of the steam engine by James Watt in the

1780’s simple applications of his machine began to spur the “Industrial

Revolution”. By the 1830’s the steam engine

had become reliable and powerful enough for transportation purposes both on

land and water.

Peter Cooper is the inventor credited with building the first steam locomotive in The US and was called “The Tom Thumb”. With this new form of transportation Railroads began appearing in every corner of the country connecting industry with suppliers and customers of every sort. Steam Locomotives were the undisputed leaders for transportation until the invention of the internal combustion engine used in automobiles and trucks in the twentieth century.

Peter Cooper is the inventor credited with building the first steam locomotive in The US and was called “The Tom Thumb”. With this new form of transportation Railroads began appearing in every corner of the country connecting industry with suppliers and customers of every sort. Steam Locomotives were the undisputed leaders for transportation until the invention of the internal combustion engine used in automobiles and trucks in the twentieth century.

It should be noted that Steam

Locomotives were built in many countries out side the United States and in fact

were in production all over the world. The United States however, built

Locomotives which were distinctive in their design and profile. Compared

to European Steam Locomotives for example, these Locomotives exemplified a

strong and independent style. They were bold and were uniquely American. Just in the United States alone over sixty companies manufactured Steam Locomotives down through the years to establish this country as a leader in Locomotive production.

Like the prehistoric Dinosaurs

the Steam Locomotives have passed on into history leaving only a few remnants

to remind us of their once mighty existence. Their silhouettes filled the

American landscape and ran through our city's and towns shaking the ground

where ever they rolled, building and transporting a nation. For the most

part this article is a pictorial of these amazing machines from the past and

the captions will tell the stories for these Steam Locomotives.

BIRTH AND EARLY LOCOMOTIVES

1830 - 1850'S

The

“Tom Thumb,” the first steam locomotive in America, reconstruction, built by

Peter Cooper. Its first successful trip was made in 1830, from Baltimore to

Ellicott Mills, Maryland.

“The

Dewitt Clinton,” the early locomotive and coaches that initiated the New York

Central System, 1831. These early applications of the steam engine for transit didn't offer many of the further refinements which would soon follow including an enclosed cab for the engineer! Notice the passenger cars; they were nothing more than "Stage Coaches" which were adapted for rail travel. Later on companies such as the "Pullman Co" would vastly improve rail passenger travel.

A

late 1830s Norris locomotive.Norris Locomotive Works, the overshadowed

neighbor of Baldwin Locomotive located just next door, and the progenitor of

Philadelphia’s preeminent rail industry, produced about a thousand railroad

engines between 1832 and 1866. It was the dominant American locomotive

producer during most of that period, and even sold its popular 4-2-0 engines to

European railways. The firm’s factory complex was located in the area

around 17th and Hamilton Streets on several acres of what had once been the

Bush Hill estate of Andrew Hamilton. The site was near the right-of-way of

the coal-hauling Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad, one of the earliest rail

lines in the US, later to become the Reading Railroad’s City Branch.

There

were two locomotives that got a ride on the turntable this morning at the Baldwin Museum Round House: a replica

of the Tom Thumb (not pictured) and a replica of the

Lafayette. The girls love the Lafayette because it's an ornery little engine -

the museum curators often talk about how it runs well whenever it wants

to, not necessarily when they want it to. http://huskerluster.blogspot.com/2011_03_01_archive.html

Found- Buried Steam Locomotive! -

Who Says Steam Locomotives Aren't Buried Under The Street?

In 1994, a circa 1879 Forney steam locomotive from New York City's Elevated Railway lines was found buried under a Garysburg North Carolina street. At the time, it was reported by the A.P. wire service. As the old proverb goes "one picture is worth 10,000 words". We have several.

Rather than a 56 foot long engine, as stated in the A.P. article, we thinks its possibly a pair of 24 foot long NYC Elevated Railway "Forneys", as described below. The following is some research done by friend of ours (Richard Fleischer), on the engine(s) buried under a North Carolina street. Likely, these locomotives are originally from New York City:

"By tracing the Rhode Island Locomotive Works construction number 750 I was able to find it was an 0-4-4T Forney type built in March 1879 for the New York Elevated Railroad where it was number 119. This D class engine had 10x16 cylinders, 42 inch drivers and weighed 37900 pounds. If it is correctly identified it could hardly be 56 feet long as was reported by the newspaper; those elevated engines were about 25 feet long. In July 1896 #119 was rebuilt to class D-2. Electrification of the elevated lines made hundreds of steam elevated engines surplus. The well made engines with years of life left in them were sold to contractors for road building and for industrial use. Number 119 was sold in December 1904 to the Conway Lumber Co. of Conway, North Carolina. So it was not used on the Atlantic Coast Line."

As can be easily seen from this photo, New York Elevated Forney locomotive bodies had quite a large surface area comprised of flat metal plate. Both the cabs and water tanks were made of flat plate. We submit this is what's clearly evident in the excavation site photos taken by the North Carolina DOT Archeology Group. An engine of this particular "pre Forney" type (Class H), the # 45, was sold to the Cliffside Lumber Co., of Cliffside, NC- about 200 miles from Garysburg, NC.

In 1994, a circa 1879 Forney steam locomotive from New York City's Elevated Railway lines was found buried under a Garysburg North Carolina street. At the time, it was reported by the A.P. wire service. As the old proverb goes "one picture is worth 10,000 words". We have several.

Rather than a 56 foot long engine, as stated in the A.P. article, we thinks its possibly a pair of 24 foot long NYC Elevated Railway "Forneys", as described below. The following is some research done by friend of ours (Richard Fleischer), on the engine(s) buried under a North Carolina street. Likely, these locomotives are originally from New York City:

"By tracing the Rhode Island Locomotive Works construction number 750 I was able to find it was an 0-4-4T Forney type built in March 1879 for the New York Elevated Railroad where it was number 119. This D class engine had 10x16 cylinders, 42 inch drivers and weighed 37900 pounds. If it is correctly identified it could hardly be 56 feet long as was reported by the newspaper; those elevated engines were about 25 feet long. In July 1896 #119 was rebuilt to class D-2. Electrification of the elevated lines made hundreds of steam elevated engines surplus. The well made engines with years of life left in them were sold to contractors for road building and for industrial use. Number 119 was sold in December 1904 to the Conway Lumber Co. of Conway, North Carolina. So it was not used on the Atlantic Coast Line."

As can be easily seen from this photo, New York Elevated Forney locomotive bodies had quite a large surface area comprised of flat metal plate. Both the cabs and water tanks were made of flat plate. We submit this is what's clearly evident in the excavation site photos taken by the North Carolina DOT Archeology Group. An engine of this particular "pre Forney" type (Class H), the # 45, was sold to the Cliffside Lumber Co., of Cliffside, NC- about 200 miles from Garysburg, NC.

In the next photo, we see a Forney likely

similar to the # 119, which was sold to the Conway Lumber Co., of Conway, NC- a

scant 20 miles from the Garysburg

excavation site. These appear to be the locomotives excavated by the

North Carolina DOT Archeology Group at Garysburg,

NC back in 1994

An early locomotive built by

William Norris for the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad

The historic “John Bull” of the

Camden & Amboy Railroad—and its train

Richard

Norris and Son was the largest locomotive maker in the United States, if not

the world, during the 1850s. Employing many hundreds of men, the factory

consisted of some ten buildings spread over several city blocks at what is now

the campus of the Community College of Philadelphia. The firm reached its

peak in 1857-58, after which time, the Norris family seems to have lost

interest in the business. Manufacturing quality and output fell during the

Civil War and the plant closed in 1866, although deliveries continued for a

year or two.

The Jupiter

(officially known as Central Pacific Railroad #60) was a 4-4-0 steam locomotive which made history as one of the two locomotives (the other being the Union Pacific No. 119) to meet at Promontory Summit during the Golden Spike ceremony commemorating the completion of the First Transcontinental Railroad.

(officially known as Central Pacific Railroad #60) was a 4-4-0 steam locomotive which made history as one of the two locomotives (the other being the Union Pacific No. 119) to meet at Promontory Summit during the Golden Spike ceremony commemorating the completion of the First Transcontinental Railroad.

The Jupiter was built in September 1868

by the Schenectady

Locomotive Works of

New York, along with three other engines, numbered 61, 62, and 63, named

the Storm, Whirlwind, and Leviathan, respectively. These four engines

were then dismantled and sailed to San Francisco, CA, where they were loaded

onto a river barge and sent to the Central Pacific headquarters in Sacramento,

then reassembled and commissioned into service on March 20, 1869.

The Jupiter was a wood burning

locomotive. The distinctive conical chimney, known as a 'balloon stack',

contained a spark arrestor. (Wikipedia.com)

A.J. Russell image of the celebration following the driving of the "Last Spike" at Promontory Summit, U.T., May 10, 1869. Because oftemperance feelings the liquor bottles held in the center of the picture were removed from some later prints. (Wikipedia.com)

Train

Roundhouse at B&O Railroad Museum Baltimore MD

1850 - EARLY 1900's

To give the Forney engine physical size

some spatial reference, the following photo shows Forney # 71 on the

Brooklyn Union Elevated line. Note the garb of the engineer is reminiscent of

that of a contemporary jockey- and it should, he was the "rider of an iron

horse".

Postcard

photo of the first locomotive in the new Grand Trunk Western Railroad shop in

Battle Creek, Michigan.

Many of the finest examples of these amazing Steam Locomotives today are found in museums located across the nation.

The

999 Steam Locomotive was a new concept in speed locomotives. Engine 999 was

assigned to haul the New York Central Railroad's brilliant new passenger train,

the Empire State Express. On May 10, 1893, the 999 became the fastest land

vehicle when it reached a record speed of 112.5 mph.

The 999 maintained the

record for a decade.

Designed

by William Buchanan and manufactured by the New York Central Railroad in West

Albany, New York in 1893, the 999 was commissioned to haul the Empire State

Express, which ran from Syracuse to Buffalo. This relatively smooth run and the

999's cutting-edge design gave the new locomotive an opportunity to make

history.

Museum

of Science and Industry - Chicago

2oth. Century and STREAMLINED

STEAM LOCOMOTIVES

Ogle Winston Link

(December 16, 1914 – January 30, 2001), known commonly as O. Winston Link, was an American photographer. He is best known for his black-and-white photography and sound recordings of the last days of steam locomotive railroading on the Norfolk & Western in the United States in the late 1950s. A commercial photographer, Link helped establish rail photography as a hobby. He also pioneered night photography, producing more than several well known examples of this style in photography. His work was highly dramatic

and captured emotion provoking images of the Steam Locomotives.

The

DT&M Roundhouse in Greenfield Village The 13,500-square-foot DT&M

Roundhouse is one of only seven in the country and the only working roundhouse

in the Midwest that serves as both an operating facility and an educational

opportunity for visitors from around the world.

Black

Hills Central Railroad Engine #7 is a 2-6-2 with tender built by Baldwin

Locomotive Works for the Ozan-Graysonia Lumber Company in 1919. The

locomotive was sold to and operated by the Caddo and Choctaw Railroad several

years later. The “Seven” was sold to the Prescott and Northwestern in Northern

Arkansas in 1938, and was acquired by the Black Hills Central Railroad in 1962.

“Suggested Unit Course in Locomotive Firing”, published

in 1944 by the Bureau of Industrial and Technical Information of the New York

State Education Department. Prepared at the Seneca Vocational High School in

Buffalo in association with the University of the State of New York, the

textbook discusses the techniques and equipment used by a fireman. The book was

probably given to my father by a railroader friend.

"The fireman of the modern

locomotive," the course begins, "must have a thorough knowledge of

firing methods that must be pursued in order to evaporate as much water into

steam as possible with every pound of coal burned." The "modern

locomotive" chosen to illustrate firing procedures was this Lima

Locomotive Works builder's photo of New York Centrals Mohawk No. 3135, sister

engine to No. 3137. She appears in this view minus the smoke deflectors visible

above.

In this illustration, the red colour represents live steam entering the cylinder, blue represents expanded (spent) steam being exhausted from the cylinder. Note that the cylinder receives two steam injections during each full rotation; the same occurs in the cylinder on the other side of the engine.

Although other types of boiler have been tried both historically and laterally with steam locomotives, their use did not become widespread, and the firebox fire-tube boiler has been the dominant source of power in the age of steam locomotion from the Rocket in 1829 to the Mallard in 1938 and beyond.

A steam locomotive with the boiler and firebox exposed (firebox on the left)

The steam locomotive, when fired up, typically employs a steel firebox fire-tube boiler that contains a heat source to the rear, which generates and maintains a head of steam within the pressurised partially water filled area of the boiler to the front.

01. Firebox 02. Ashpan03. Water (inside the boiler)

04. Smokebox 05. Cab

06. Tender 07. Steam Dome

08. Safety Valve

09. Regulator Valve

10. Superheater Header in smokebox

11. Piston 12. Blastpipe

13. Valve Gear 14. Regulator Rod

15. Drive Frame 16. Rear Pony Truck

17. Front Pony Truck

18. Bearing and Axlebox

19. Leaf Spring 20. Brake shoe

21. Air brake pump

22. (Front) Centre Coupler,

23. Whistle 24. Sandbox.

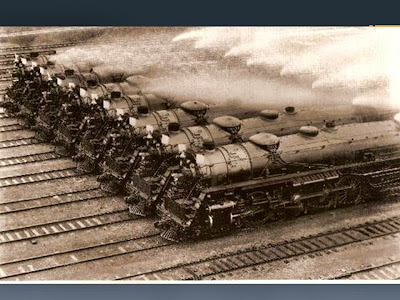

The Baldwin Locomotive Works was founded in 1831 by Matthias Baldwin. The original plant was on Broad street in Philadelphia, PA where the company did business for 71 years until it moved in 1912 to a new plant in Eddystone. Various partnerships during this period resulted in a number of name changes. It was known as Baldwin, Vail & Hufty (1839-1842); Baldwin & Whitney (1842-1845); M. W. Baldwin (1846-1853); and M. W. Baldwin & Co. (1854-1866). After Baldwin's death in 1866 the firm was known as M. Baird & Co. (1867-1873); Burnham, Parry, Williams & Co. (1873-1890); Burnham, Williams & Co. (1891-1909); it was finally incorporated as the Baldwin Locomotive Works in 1909. Westinghouse Corporation bought Baldwin in 1948. In 1950 the Lima-Hamilton Corporation and Baldwin merged. In 1956 the last of some 70,541 locomotives was produced. An aerial view of the Baldwin plant is shown on the right. Today, F. W. Hake's Trucking Co. occupies this land.

Baldwin Locomotive Works - Confederation locomotives Test ..

Baldwin's name is well known to railway enthusiasts and quickly connected with American steam locomotives.

And it is quite true, but enclose much more and is synonymous with one of the most spectacular and bizarre industrial histories. The beginning of a firm that would become the largest manufacturer of locomotives in the world could not be more modest and casual. The story begins with Mr. Matthias Baldwin, a jeweler-goldsmith who ran a small business in the city of Philadelphia USA, but would be his great manual dexterity and passion for mechanics who soon would mark his future definitely. formed In 1825 a small company with a mechanic acquaintance to engage in the manufacture of binders and printing cylinders.

Soon after he designed and built a small steam engine for their own use in the workshop. The results were great and soon caught the attention of customers and neighbors, some of whom he was commissioned to make other units for different applications. All this spurred him to leave precious metals and definitely devote his full attention since the design and construction of steam engines. Six years later, in 1831, the Philadelphia Museum commissioned the construction of a miniature steam locomotive for a cultural display, making it probably in the first railway modeller history. Their model was so successful that caught the attention of a small area railway company who commissioned the construction of a life-size locomotive to operate on a short railway line in the city.

As aware of the size of the order and of the difficulties and gaps that have to face, decided to travel to New Jersey where a neighborhood store Bordentown parts were kept in a British steam locomotive (John Bull) imported by the Amboy Railroad Company and waiting to be mounted. There thoroughly inspected all parts, taking measurements and references that would serve as guidance when started soon after making your first purchase. machining difficulties it had to face not easily imaginable by mechanical or modelers today, accustomed as we are to have excellent machines and accessories.

At that time the general tools and precision in particular were very difficult to obtain. The cylinder bores should be nailed through blades in wooden drums they were centered and rotated by hand, aides knew practically nothing and should be instructed in every step of manufacturing, finishing Baldwin as the same which was much more delicate tasks. Finally his first locomotive, the Old Ironsides , four-wheel, five tons of weight, chassis and wheel spokes made of wood was successfully tested in late 1832 by way of Philadelphia, which worked perfectly for many years. From then until his death in 1866, this large industrial pioneer locomotives built many more small workshop in his city of just over 800 square meters, then bequeathing to his heirs an already powerful industry right track, in addition to the fond memory of a life devoted also to do many philanthropic and the rights of the Afro-American and other disadvantaged minorities.

In 1906, the Baldwin factory production was booming, so much of its dependencies were installed in an area of 2.5 m / 2 in the nearby coastal town of Eddystone in Pennsylvania. Subsequently, and in 1928, ran to relocate and expand the rest of the facility, reaching even have its own port and a fleet of merchant ships for the export of their rolling stock. During the nineteenth century were made, among others, genoas thousands of famous 2-2-0, though no doubt were the early decades of the twentieth century that marked the golden age of a company that soon became the first manufacturer in the United States and around the world.

Their locomotives steam were synonymous with strength and reliability, rolling in almost all American railroads and also exporting to almost all countries of the world. was at that time (1919) when the newly formed Steel Mining Company of Ponferrada and, due to the impossibility purchase in European markets by the difficulties caused by the First World War, the firm commissioned ten locomotives Baldwin 1-3-1 Prairie tank type and distribution of saturated steam valves Walshchaerts flat. The company received the order in late 1919 , promising to take the ten locomotives in Eddystone spring li On July 08 2009

C

& O Allegheny #1601 Built in 1941 and weighing in at 600 tons, this was one

of the largest steam-powered locomotives ever built.

Santa

Fe steam locomotive #3768 entered service with the Santa Fe Rail Road in 1938

New

York, Chicago & St. Louis No. 757 --Nickel Plate Road

Lima 2-8-4 Blt

1944. First locomotive donated to RR Museum of PA.

New York Central "Commodore

Vanderbilt" - 1935

NYC's first steam stream liner was designed by Carl Kantola (with wind tunnel testing at Cleveland's Case Institute) and fabricated as a converted Hudson in the railroad's shops near Albany. The Commodore Vanderbilt was the second-string New York - Chicago run to the premier 20th Century Limited.

The streamlined trains featured in Part 1 of this series were diesel powered. At the time -- the mid-1930s -- most American locomotives were steam-powered, so the easiest, cheapest means of hopping on the streamlining bandwagon was to give existing locomotives streamlined cladding. And that's what some major railroads did while waiting to convert to diesel power, a process that moved into high gear in the 1940s.

Two of America's richest and most famous railroads were the New York Central and the Pennsylvania Railroad. The key passenger run for each was New York - Chicago, linking the nation's largest and next-largest cities.

NYC's first steam stream liner was designed by Carl Kantola (with wind tunnel testing at Cleveland's Case Institute) and fabricated as a converted Hudson in the railroad's shops near Albany. The Commodore Vanderbilt was the second-string New York - Chicago run to the premier 20th Century Limited.

The streamlined trains featured in Part 1 of this series were diesel powered. At the time -- the mid-1930s -- most American locomotives were steam-powered, so the easiest, cheapest means of hopping on the streamlining bandwagon was to give existing locomotives streamlined cladding. And that's what some major railroads did while waiting to convert to diesel power, a process that moved into high gear in the 1940s.

Two of America's richest and most famous railroads were the New York Central and the Pennsylvania Railroad. The key passenger run for each was New York - Chicago, linking the nation's largest and next-largest cities.

Having learned from the S1s, the

Pennsylvania ordered 4-4-4-4 locomotives, designated T1s, from Baldwin. The

first were delivered in spring, 1942, enshrouded by Raymond Loewy in what

became known as the “shark-nose” style. Not as pretty as the S1, the T1s

operated well enough that the Pennsy

eventually bought 50 from Baldwin.

Pennsylvania Railroad T1

The T1 was another Loewy creation, but one that saw service starting in 1942. It was a cleaned-up version of a normal steam locomotive with an aggressive "face" that looks like it was not an optimal case of streamlining, though the rounded "splitter" form in front of the boiler must have had less air resistance than a regular flat boiler section did. The T1 was the last major steam-powered streamlined locomotive type built in America.

Pennsylvania Railroad T1

The T1 was another Loewy creation, but one that saw service starting in 1942. It was a cleaned-up version of a normal steam locomotive with an aggressive "face" that looks like it was not an optimal case of streamlining, though the rounded "splitter" form in front of the boiler must have had less air resistance than a regular flat boiler section did. The T1 was the last major steam-powered streamlined locomotive type built in America.

On the West Coast, the Southern

Pacific was another railroad that didn’t seem to trust Diesels, so when it

streamlined its San Francisco-Los Angeles trains, it ordered semi-streamlined

Northern (4-8-4) locomotives from Lima (the “Chrysler of steam locomotive

manufacturers”). The first entered service in March, 1937, and eventually SP

would own 36 of these locomotives. Despite their lack of full streamlining,

they were very popular due to their bright orange-and-red color scheme. As previously noted,

the SP also semi-streamlined some older (1913) Pacifics

for its Sunbeam train from Dallas to Houston.

Jeff Koons

'Train' Sculpture Could Be Suspended Above The High-Line

Artist Jeff Koons

could bring a full-size replica of a 1943 Baldwin 2900 steam locomotive to New

York City's High Line. The train wouldn't be on the old tracks of the former

elevated rail line, however, but rather suspended above, dangling from a crane:

Entitled "Train," the

70-foot sculpture would also spin its wheels, blow a horn and emit steam.

"We’ve had a crush on the

‘Train’ for a while now,” Robert Hammond, one of the founders of Friends of the

High Line, told The New York Times.

“To me, it looks very industrial and sculptural. The craftsmanship that went

into these industrial engines is quite beautiful."

Jeff Eccles,

former director of the Public Art Fund, told The

Times,

"Like any Jeff Koons work, it is strikingly simple,

ingenious and probably one of the most amazing things you’ll ever see,” adding,

“It’s like picking up a dog by its tail, with the legs still running,” he

added. “In some ways, it’s suspended between the past and the future. Were one

to commission a site-specific work for the High Line, you probably couldn’t

have come up with a better piece.”

Posted: 03/27/2012 11:11 am

Updated: 03/27/2012 2:44 pm – “The Huffington Post”

"The Atlantic"

A Gorgeous Photographic Elegy to the Last Great Steam Train

What does the world around us look like? Do we have big cities with tall skyscrapers, sprawling suburbs with lawns and garages, or small towns with dense little centers?

Few things dictate our built environment as much as the technology of transit -- what we use to move people and things. Over the course of the 20th century, that technology shifted dramatically, from horses and trains to cars and planes, but it did so gradually, with jumps and starts, unevenly, with older technologies persisting in certain pockets longer than in others.

Steam engines are mythic beasts -- massive, belching beasts that, in the 1950s, were on their way to becoming extinct. In 1946, steam locomotives moved 78 percent of American rail-freight traffic. By 1951, that number fell to 31, and by 1959, it was all but gone -- less than one percent.

Diesel wasn't the only threat: The rise of the automobile and plane meant the decline of passenger rail more generally. Though modern diesel freight trains still run along much of the N&W, many of the towns have no passenger rail service, shifting the center of town life away from the train station, toward the roads and stores our cars service so well.

But before these great machines totally died out, they were visited by O. Winston Link, one of the greatest railroad photographers of all time, whose work along the N&W is collected in a new book O. Winston Link: Life Along the Line (Abrams), with accompanying text by rail historian Tony Reevy. Link's photographs are recognized for their cinematic lighting, their ability to tell a whole story in a single image, and, often, their nighttime settings, a few examples of which are selected below.

According to Reevy, more than anything, the decline of steam locomotives had a major and direct impact on the workers who ran and maintained these great machines. "The steam engine," he wrote to me, "was a labor-intensive beast. Each locomotive required an engineer and a fireman and steam engines all had to be operated separately; so, two steam engines, a 'double-header,' required two engineers and two firemen." Diesel units, on the other hand, can be joined together and operated by one engineer. Steam firemen were no longer needed.

"What is more," Reevy continued, "steam engines were maintenance intensive, requiring frequent lineside supplies of water and coal, frequent light maintenance by repair employees in specialized facilities ('roundhouses') and fairly frequent heavy repairs in shop facilities." Much of the book showcases these employees, men at work on the trains, but whose jobs disappeared with the steam engines.

Reevy says that beyond the direct effects on labor, the biggest changes in the region were not brought about by the rise of diesel but by the decline of passenger rail with the arrival of the private automobile and jet travel. In perhaps what is Link's most famous photograph (it even made a cameo in a 1998 Simpsons episode, "Dumbbell Indemnity"), all three forms of transportation co-exist, one shot that captures the shifting transit landscape of mid-20th-century America.

Another of Link's more famous works, The Birmingham Special, also captures that juxtaposition, a sly irony filling out the narrative: Here is this monster, this steam-breathing beast, and here is the small bug, the car, that undid it.

It is this shift, Reevy writes, that "had a greater impact on the small towns of the Norfolk & Western's service area than the passing of steam. Even in 1950, most lineside communities on the N&W, and on American railroads, had railroad stations that provided passenger, freight, express and Western Union (telegram) service.

Elderly folks, children, the poor, could travel without being dependent upon access to a private automobile. The station ... often served as a, or the, community center. As railroad passenger service faded, small towns ... were left isolated, 'off the beaten track.' The waning of American transportation choices has combined with the relative growth of large cities, the decline of small farms, the coming of big box stores and a number of other factors to disadvantage many such communities compared to urban areas.

All of this totaled up to a shift in not just landscape but culture. Steam engines, Reevy wrote to me, were "highly reflected in our music, our folklore, and our art. Perhaps due to its animate appearance (seeming to breathe, with an air pump that sounds like a heartbeat and so on), the steam locomotive added a richness to the American cultural scene that the diesel locomotive does not." In losing steam power, America lost that particular artistic inspiration, that icon. "At least," Reevy reflected, "even with diesel locomotives, we still have whistles in the night."

Steam may be just a bunch of hot air, but that hot air packed a lot of power, fueling a region and the people who lived there for decades. In Link's images we see that power, lighting up a night sky and a lonely town.

The above article from "The Atlantic" is one of so many tributes to O. Winston Link and the days of the Steam Locomotive which have been published over the years. It is only a small example of the landscape and history of Steam Locomotives when they were such a large part of the American landscape when the country was a lot younger.

Most of this article has discussed the classic Steam Locomotive build as they were the most widely used and many different models were manufactured down through the years. So many of these Locomotives were modified, improved and developed during the history of Steam Locomotives that we have in no way been able to illustrate all of them but only a few representatives of the magnificent machines over the years!

There were a different breed of Steam Locomotives however which should be mentioned. They were designed by Ephraim Shay and built by the Lima Locomotive works. These Locomotives were a smaller gauge, meaning a smaller wheel base, and used a geared driver. If the conventional Steam Locomotive was thought of as the "Iron Horse" than it could be said the Shay Locomotive was the "Iron Mule" of railroading! The following is a general description of these Locomotives from Wikipedia:

Lima - Shay Locomotives

Shay locomotives had regular fire-tube boilers offset to the left to provide space for, and counterbalance the weight of, a two or three cylinder "motor," mounted vertically on the right with longitudinal drive shafts extending fore and aft from the crankshaft at wheel axle height. These shafts had universal joints and square sliding prismatic joints to accommodate the swiveling trucks. Each axle was driven by a separate bevel gear, with no side rods.

The strength of these engines is that all wheels, including, in some engines, those under the tender, are driven so that all the weight develops tractive effort. A high ratio of piston strokes to wheel revolutions allowed them to run at partial slip, where a conventional rod engine would spin its drive wheels and burn rails, losing all traction.

Shay locomotives were often known as sidewinders or stemwinders for their side-mounted drive shafts. Most were built for use in the United States, but many were exported, to about thirty countries, either by Lima, or after they had reached the end of their usefulness in the US.

"wikipedia.com"

While

a logger, Shay wanted to find a new way to get logs to the mill besides

floating them on a river. Subsequently, about 1877 he developed the idea

to have an engine sit on a flat car with a boiler, gears and trucks that could

pivot. The Shay locomotive was born. They were used extensively in the logging, mining and locations where access was limited for the traditional Steam Locomotives. Lima Locomotive Works of Lima, Ohio built

Ephraim Shay's prototype engine in 1880 and Shay was issued a patent for the

basic idea in 1881.

Shay

locomotive with log train making smoke rounding a mountain curve, an antique

steam engine running at Cass Scenic Railroad, a tourist attraction in Cass,

West Virginia, USA.

"The Atlantic"

A Gorgeous Photographic Elegy to the Last Great Steam Train

Photographs of the Norfolk and Western Railway, America's last great steam railroad.

1954 Norfolk and Western Railway System Map (Norfolk and Western Historical Society)

|

| Ogle Winston Link |

Winston

Link (left) was born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1914, the son of a school

teacher. Early on, Link showed an aptitude for technology, and his father, a

demanding man but a good instructor introduced him to a variety of options. The

elder Link trained his son to handle tools well and encouraged his interest in

photography. Link was also a pioneer of the Electronic Flash and was a master of the technique known as "painting with light". It was at this time that he also developed an interest in steam

railroading which was to remain with him for life. Link attended the

Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn, where he was a good student and a popular

one, being particularly well known for his practical jokes. He graduated in

1937 with a degree in civil engineering, but photography was to claim him

before engineering could.

What does the world around us look like? Do we have big cities with tall skyscrapers, sprawling suburbs with lawns and garages, or small towns with dense little centers?

Few things dictate our built environment as much as the technology of transit -- what we use to move people and things. Over the course of the 20th century, that technology shifted dramatically, from horses and trains to cars and planes, but it did so gradually, with jumps and starts, unevenly, with older technologies persisting in certain pockets longer than in others.

One of those holdouts was the region stretching from the coal mines of Ohio, West Virginia, and western Virginia, out east to the Norfolk port, from where the coal was shipped around the country and around the world. There, the Norfolk and Western Railway continued to run on steam -- not the more newfangled diesel-electric -- until May of 1960, surviving both because of an allegiance to the coal mines that fed it, and because it ran classes of locomotives that were some of the finest ever made.

Steam engines are mythic beasts -- massive, belching beasts that, in the 1950s, were on their way to becoming extinct. In 1946, steam locomotives moved 78 percent of American rail-freight traffic. By 1951, that number fell to 31, and by 1959, it was all but gone -- less than one percent.

Diesel wasn't the only threat: The rise of the automobile and plane meant the decline of passenger rail more generally. Though modern diesel freight trains still run along much of the N&W, many of the towns have no passenger rail service, shifting the center of town life away from the train station, toward the roads and stores our cars service so well.

But before these great machines totally died out, they were visited by O. Winston Link, one of the greatest railroad photographers of all time, whose work along the N&W is collected in a new book O. Winston Link: Life Along the Line (Abrams), with accompanying text by rail historian Tony Reevy. Link's photographs are recognized for their cinematic lighting, their ability to tell a whole story in a single image, and, often, their nighttime settings, a few examples of which are selected below.

Train #2 arrives at the Waynesboro Station, Waynesboro, Virgnia, April 14, 1955 (© Conway Link; courtesy of the O. Winston Link Museum)

According to Reevy, more than anything, the decline of steam locomotives had a major and direct impact on the workers who ran and maintained these great machines. "The steam engine," he wrote to me, "was a labor-intensive beast. Each locomotive required an engineer and a fireman and steam engines all had to be operated separately; so, two steam engines, a 'double-header,' required two engineers and two firemen." Diesel units, on the other hand, can be joined together and operated by one engineer. Steam firemen were no longer needed.

Electrician J. W. Dalhouse, a close-up view. Shaffers Crossing, Roanoke, Virginia, March 19, 1955 (© Conway Link; courtesy of the O. Winston Link Museum)

"What is more," Reevy continued, "steam engines were maintenance intensive, requiring frequent lineside supplies of water and coal, frequent light maintenance by repair employees in specialized facilities ('roundhouses') and fairly frequent heavy repairs in shop facilities." Much of the book showcases these employees, men at work on the trains, but whose jobs disappeared with the steam engines.

Lubricating wristpin. Bluefield, West Virginia, June 20, 1955 (© Conway Link; courtesy of the O. Winston Link Museum)

Reevy says that beyond the direct effects on labor, the biggest changes in the region were not brought about by the rise of diesel but by the decline of passenger rail with the arrival of the private automobile and jet travel. In perhaps what is Link's most famous photograph (it even made a cameo in a 1998 Simpsons episode, "Dumbbell Indemnity"), all three forms of transportation co-exist, one shot that captures the shifting transit landscape of mid-20th-century America.

Hotshot Eastbound. Iaeger, West Virginia, August 2, 1956 (© Conway Link; courtesy of the O. Winston Link Museum)

Another of Link's more famous works, The Birmingham Special, also captures that juxtaposition, a sly irony filling out the narrative: Here is this monster, this steam-breathing beast, and here is the small bug, the car, that undid it.

The Birmingham Special crosses Bridge 201. Near Radford, Virginia, December 17, 1957 (© Conway Link; courtesy of the O. Winston Link Museum)

It is this shift, Reevy writes, that "had a greater impact on the small towns of the Norfolk & Western's service area than the passing of steam. Even in 1950, most lineside communities on the N&W, and on American railroads, had railroad stations that provided passenger, freight, express and Western Union (telegram) service.

Elderly folks, children, the poor, could travel without being dependent upon access to a private automobile. The station ... often served as a, or the, community center. As railroad passenger service faded, small towns ... were left isolated, 'off the beaten track.' The waning of American transportation choices has combined with the relative growth of large cities, the decline of small farms, the coming of big box stores and a number of other factors to disadvantage many such communities compared to urban areas.

Train #17, the Birmingham Special, arriving at Rural Retreat. Rural Retreat, Virginia, December 26, 1957 (© Conway Link; courtesy of the O. Winston Link Museum)

All of this totaled up to a shift in not just landscape but culture. Steam engines, Reevy wrote to me, were "highly reflected in our music, our folklore, and our art. Perhaps due to its animate appearance (seeming to breathe, with an air pump that sounds like a heartbeat and so on), the steam locomotive added a richness to the American cultural scene that the diesel locomotive does not." In losing steam power, America lost that particular artistic inspiration, that icon. "At least," Reevy reflected, "even with diesel locomotives, we still have whistles in the night."

Hester Fringer's living room on the tracks. Lithia, Virginia, December 16, 1955 (© Conway Link; courtesy of the O. Winston Link Museum)

Steam may be just a bunch of hot air, but that hot air packed a lot of power, fueling a region and the people who lived there for decades. In Link's images we see that power, lighting up a night sky and a lonely town.

Ghost Town. Stanley, Virginia, February 1, 1957 (© Conway Link; courtesy of the O. Winston Link Museum)

"The Atlantic"

The above article from "The Atlantic" is one of so many tributes to O. Winston Link and the days of the Steam Locomotive which have been published over the years. It is only a small example of the landscape and history of Steam Locomotives when they were such a large part of the American landscape when the country was a lot younger.

Diesel Locomotives have now replaced the old Steam Locomotives which roam the rails throughout the country. Railroad companies have consolidated as the demand for rail and train travel are now diminished by Automobile, Trucking and Jet Liner Air travel. The railroads still exist today moving freight from coast to coast and some tourist lines are still running for sight seers providing those who seek the luxury of train travel from yesteryear.

Those Steam Locomotives still exist on the pages of history and the music which sings of their poetry; the rhythm of their drivers. We only have but to seek out the few remaining preserved Locomotives; for they will still be with us for some time in the future. We hope that you have loved reading and seeing this article as we have loved writing and putting together this photo essay. I'm Felicity Blaze Noodleman and maybe we'll meet some where between New York and California on a ride for thrill seekers with a Locomotive known as "the Iron Horse"!

Tell your friends and associates about us!

It's easy! Just copy and paste me into your email!

* “The Noodleman Group” is pleased to announce that we are now carrying a link to the “USA Today” news site.We installed the “widget/gadget” August 20, and it will be carried as a regular feature on our site.Now you can read“Noodleman” and then check in to “USA Today” for all the up to date News, Weather, Sports and more!Just scroll all the way down to the bottom of our site and hit the “USA Today” hyperlinks.Enjoy!

The Noodleman Group is on Google "Blogger"!

No comments:

Post a Comment